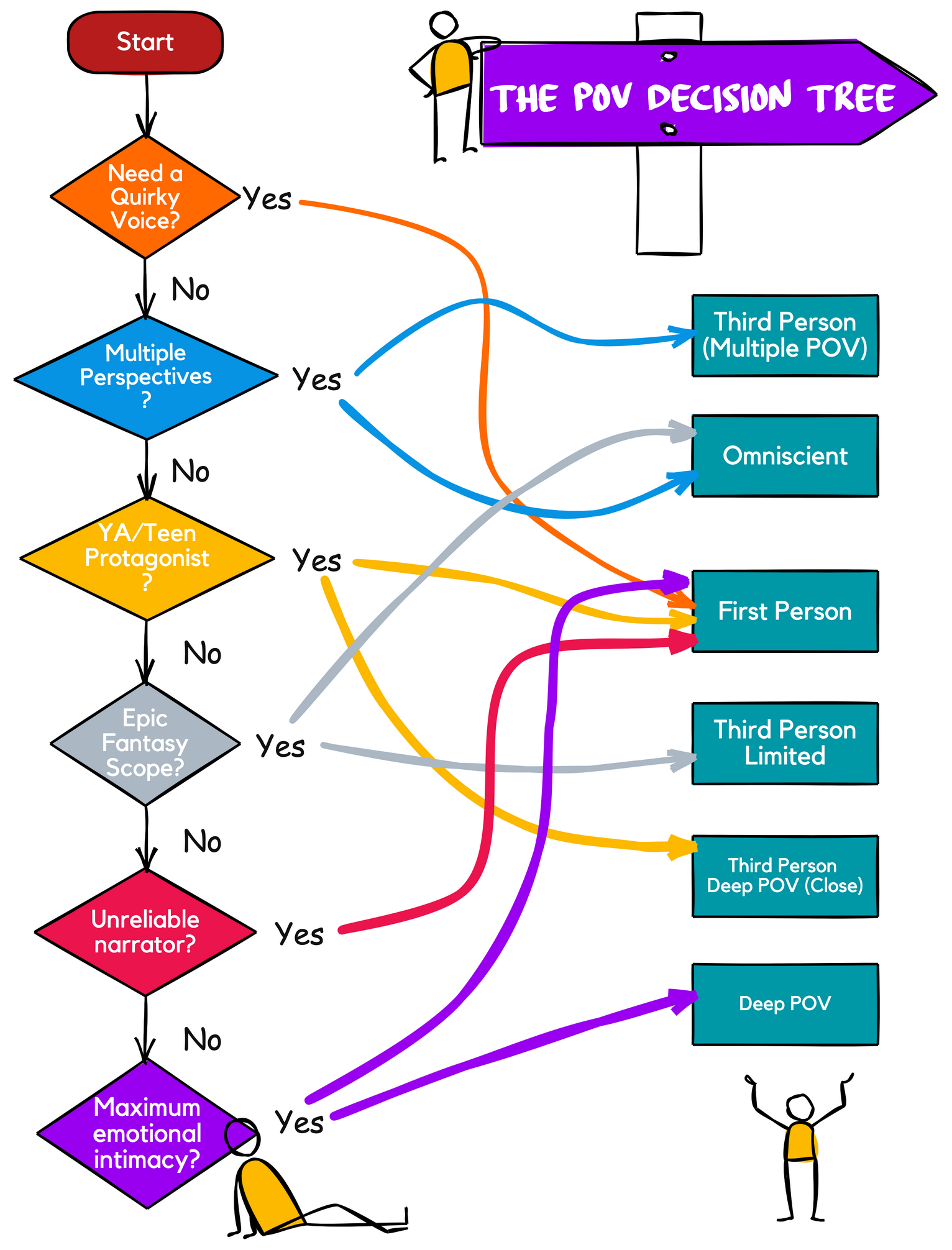

Mastering point of view is one of the most consequential decisions a writer will ever make. It dictates not just the angle from which the story is told but also who the audience trusts, how close they feel to the narrative, and which secrets remain out of reach. Imagine pages that envelop the reader in intimacy, others that tease with mystery, and still more that allow readers to float above the story world, observing but never interfering. This is the writer's true superpower.

What Is Point of View?

Point of view, at its heart, is that vantage point through which the story unfolds. Sometimes the author plants the reader firmly inside a protagonist's mind, letting every thought and emotion echo in their ears. "I don’t know if I can do it," whispers Katniss as she readies herself for the Games. When written in first person, the reader shares both her fear and determination.

Other times, the reader stands slightly further back, looking over a character’s shoulder. In a third person limited viewpoint, the narrator zooms in close to one person's experiences and thoughts, but the rest remain mysterious. Consider a suspense scene: "He gripped his keys, hoping nobody would notice his shaking hands. He didn’t see the shadow moving behind the curtains." We know what our protagonist notices, and what he misses.

Omniscient point of view swings the doors wide open, granting the audience a god-like perspective. The narrator may dip into the minds of several characters, offering insights, secrets, and commentary unavailable to any one individual. It's as if the story itself is whispering, "Mary hoped Harold would finally propose, but Harold—unbeknownst to her—had forgotten the ring in his desk drawer." The audience is always a beat ahead of the characters, savoring dramatic irony and layered storytelling.

Sometimes writers experiment further, using second person to cast the reader in the lead role. "You enter the room. The scent of lavender surrounds you, and the door locks behind you." Here, the lines blur, and the reader becomes both protagonist and audience—a technique often found in adventurous or experimental fiction.

Refer to POV Quick Reference Sheet

When to Use Each POV: Dialogue & Prose Examples

"I can’t believe you did that," Sarah muttered, her voice trembling. When the story is told through Sarah’s eyes, every small sensation—the sting of embarrassment, the weight of regret—comes alive for the reader. This intimacy is the hallmark of first person. In contrast, if the narrative shifts to third person limited, we step slightly outside: "Sarah stared at her reflection, wondering if she would ever forgive herself."

Consider a mystery novel where each chapter reveals a different detective’s deduction. By rotating the third person limited perspective, the writer maintains suspense, letting the reader experience each clue through fresh eyes. Meanwhile, omniscient narration allows us into every character’s head: "John considered the evidence. Across the city, Detective Vega jotted a theory in her notebook. Neither realized that the culprit had already fled town."

An unreliable narrator can transform a story into an intricate puzzle. Holden Caulfield assures us repeatedly, "I’m the most honest guy you’ll ever meet," but as his tale spirals out of control, readers learn to question his every assertion. Sometimes the narrator deceives deliberately, sometimes they're simply mistaken or unaware. Imagine a scene: "Mother says I was a difficult child, but I remember being quiet as a mouse." Is the truth being told—or just one version of it?

Genre Expectations & What POV Brings to the Table

Different genres lean on different points of view for good reason. Young adult fiction often prefers first person; its immediacy helps readers relate deeply to protagonists’ struggles. Epic fantasy and historical sagas thrive in third person limited or omniscient, offering sweeping perspectives and multiple intertwined lives. Romance frequently alternates perspectives, bringing both lovers' hopes and fears to light. Mysteries might employ a single first-person detective or alternate viewpoints to heighten suspense and drama. Writers should be aware of these traditions but also feel empowered to break them—with purpose.

Refer to Genre Expectations Worksheet

The Dangers and Rewards of Narrative Distance

Imagine storytelling as a camera lens. Pull back for a panoramic view: "There was a party in the old manor, laughter echoing through its halls." Tighten focus for an emotional close-up: "Emily felt her heart hammer in her chest as she glimpsed the stranger across the room." Masterful writers adjust this lens, moving between objective observation and deep immersion in a character’s psyche. The closer the narrative distance, the more the reader feels—but too close for too long can suffocate with unrelenting emotion.

Refer to the narrative Distance Scale Worksheet

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them (A Writer’s Dialogue)

"Why does this scene feel so muddled?" Jane asked.

Mark thumbed through her draft. "It’s head-hopping. One moment we're in Sarah’s mind, then we leap to John's without warning. Readers crave consistency. It's like jumping from one film to another in the middle of a scene."

Jane nodded. "And these filter words—'she saw,' 'he heard,' 'I felt'—create a distance I don’t want. How can I write more intimately?"

"Try showing instead of telling," Mark suggested. "Instead of 'she saw the storm approaching,' try 'Black clouds swallowed the horizon.' It's direct, and the reader experiences it as the character does."

How To Choose Your POV (Narrative Framework Example)

Imagine you're planning a heist story. Ask yourself: Who has the most to lose in each scene? Do genre conventions steer your choice? What emotional effect do you want? For a tense escape, perhaps tight third person limited with the protagonist’s every heartbeat in focus. For a broader tale exploring the motives of all players, omniscient might serve best.

Consider writing out a page in more than one point of view, then reading aloud to hear which feels most authentic.

Want a copy of this graphic? Download it with the button below

The Unreliable Narrator: Types, Examples, and Mastery

Understanding the Unreliable Narrator

An unreliable narrator is not simply a character who lies. Rather, it's a narrative perspective that cannot be fully trusted to tell the truth as readers expect it. The unreliability may stem from intentional deception, mental illness, ignorance, bias, or simple human limitation. When wielded expertly, the unreliable narrator becomes one of a writer's most potent tools—a device that engages readers in the act of detective work, questioning every assertion and uncovering deeper truths beneath the surface.

The beauty of this technique lies in its subtlety. A reader should never feel confused or frustrated by the narrative; instead, they should gradually suspect that something is amiss, then delight as they piece together the real story. The finest unreliable narrators are captivating—so charming, so insightful, or so sympathetic that we want to believe them, even as evidence accumulates that we shouldn't.

Click the button below to download this graphic

The Seven Types of Unreliable Narrators

1. The Liar: Intentional Deception

The Liar knows the truth and deliberately distorts it. This narrator has something to gain from their falsehoods—protection, sympathy, power, or revenge. Think of Amy in Gillian Flynn's Gone Girl. Throughout much of the novel, Amy narrates events with apparent sincerity, painting herself as a victim. Only gradually do readers discover that she has orchestrated her own disappearance and framed her husband for murder. Her narration was always a calculated performance.

How to use it properly: The key is planting clues that observant readers can catch. Amy's "diary" entries, for instance, contain small contradictions—events that don't quite align with what other characters report. Include moments where the narrator's story strains credibility, moments where they become defensive or conveniently vague. Most crucially, decide whether the deception will be fully revealed, partially exposed, or left ambiguous. This choice shapes the entire reading experience.

Example dialogue: "I've never hurt anyone in my life," the character insists. But three chapters earlier, readers witnessed them deliberately sabotaging a rival's career. The lie is obvious in hindsight, but in the moment of reading it, doubt creeps in.

2. The Madman: Severe Mental Illness or Trauma

The Madman does not lie consciously; rather, their perception of reality is distorted by psychological illness, trauma, or neurological condition. In Chuck Palahniuk's Fight Club, the unnamed narrator suffers from dissociation and a fractured psyche. He genuinely believes his account—yet much of what he reports is either hallucination or interpretation filtered through a deeply troubled mind.

How to use it properly: The narrator should believe their own story absolutely. They're not trying to deceive anyone; they're simply reporting what they experience. Your job is to reveal their unreliability through inconsistencies, through other characters' confused reactions, or through a dramatic revelation that reframes everything. The reader should feel a mix of sympathy and unease, never quite certain which parts of the narrative are real.

Example in prose: "The walls were breathing again, expanding and contracting like lungs. Nobody else seemed to notice. I mentioned it to Sarah, and she just stared at me with that worried expression she gets. I knew she thought I was crazy. But I wasn't. The walls were definitely breathing."

3. The Naïf: Innocence and Limited Understanding

The Naïf is simply too young, too inexperienced, or too sheltered to understand the full truth of situations. In Emma Donoghue's Room, young Jack narrates from inside a single locked room, unaware of the larger world or even the full extent of his circumstances. His innocence is absolute. He doesn't lie; he simply doesn't know.

How to use it properly: The Naïf works beautifully for exploring gaps between perception and reality. What the narrator believes to be normal might horrify readers. What they interpret as an adventure might be something far darker. The power lies in the contrast—we see both the child's innocent interpretation and, beneath it, the disturbing truth. Use other characters' dialogue and reactions to hint at what the Naïf cannot grasp.

Example in prose: "My mother says I'm special and that I'll understand things when I'm older. The men who visit are nice, but she always makes me go to the back room. I don't mind. I read my books and wait. I think that's what all mothers do."

4. The Picaro: Exaggeration and Embellishment

The Picaro is a charming trickster who loves storytelling so much that truth bends under the weight of entertainment. They're not trying to hide a dark secret; they're simply incapable of telling a story the plain way when a more exciting version exists. Daniel Defoe's Moll Flanders and Mark Twain's Huck Finn both embellish, though usually without malice.

How to use it properly: The Picaro's unreliability is often lighter than other types, making them excellent for humorous or satirical fiction. Readers often enjoy being spun a yarn, particularly when they suspect the narrator of doing so. Reveal the true events gradually, or let them remain mysterious—the humor often comes from the contrast between the narrator's version and what actually happened. Use dialogue from other characters to provide reality checks.

Example in prose: "I've fought seventeen different men in my time, each one taller and meaner than the last. The tallest one nearly reached the ceiling. Well, that might be an exaggeration. Perhaps twelve men. Or maybe five, but those five were really something."

5. The Clown: Playing Games with Truth

The Clown treats narrative as theater, deliberately toying with reader expectations. Laurence Sterne's Tristram Shandy is a masterclass in this technique—the narrator constantly breaks the fourth wall, addresses the reader directly, and plays tricks with structure and pacing. The unreliability is intentional and often acknowledged.

How to use it properly: This type works best in experimental or metafictional works where readers expect playfulness. The narrator might acknowledge their own unreliability or wink at the audience. The fun lies not in discovering deception but in experiencing the narrative game itself. Be wary of overusing this technique in mainstream fiction—many readers find it frustrating rather than clever.

Example in prose: "Now, I could tell you what happened next, but wouldn't it be more interesting if I went back three weeks first? Or perhaps I should skip ahead? You, dear reader, decide. Actually, no, scratch that—I'm the writer, and we're doing this my way. But I did appreciate you considering my offer."

6. The Biased: Personal Prejudice and Perspective

The Biased narrator does not intentionally lie, but their personal prejudices, hopes, and fears color everything they report. In George R.R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire, different point-of-view characters interpret the same events through radically different lenses. Daenerys sees herself as a liberator; to others, she appears as a potential tyrant. Each is telling their truth—their biased truth.

How to use it properly: This is perhaps the most subtle form of unreliability. The narrator reports events accurately but interprets them through a distorted lens. Show the same events from multiple perspectives to reveal the unreliability, or let readers gradually notice how the narrator's judgments seem off. Use dialogue and action to subtly contradict the narrator's assessments of other characters.

Example in prose: "He was always so selfish, always thinking of himself first. When he told me he couldn't come to my birthday party because he was sick, I knew he was lying. He just didn't care enough. It wasn't until weeks later that I learned about his hospitalization."

7. The Impaired: Substance Abuse, Memory Loss, or Altered States

The Impaired narrator's unreliability stems from external factors—drugs, alcohol, sleep deprivation, or a neurodegenerative condition. Paula Hawkins' The Girl on the Train features Rachel, an alcoholic woman whose memory is fragmented and unreliable. She experiences blackouts, misremembers events, and cannot be certain what she's actually witnessed.

How to use it properly: Show the impairment honestly. If your narrator is drunk, let their narration become slurred or unreliable in real time. If memory is the issue, use inconsistencies and self-doubt to signal that something is wrong. Other characters might reference events the narrator has forgotten or misremembered. The pathos often comes from watching the narrator struggle against their own limitations.

Example in prose: "I remember the party. Or do I? The scotch was smooth. There was a woman in a red dress. Or was she wearing blue? I woke up with a headache and three missed calls from my sister. What did I do last night? I'm not entirely sure."

How to Write Unreliable Narrators Without Confusing Your Readers

The greatest challenge with unreliable narrators is maintaining engagement without frustrating the audience. Here are the essential principles:

Plant Clues Early and Often. Observant readers should be able to catch hints that something is off. If your narrator claims to be honest, show them lying about small things. If they claim to have a perfect memory, contradict them gently. These breadcrumbs create a delightful "aha!" moment when readers realize they've been misled.

Make the Narrator Compelling. Readers will tolerate unreliability if they care about the character. Amy in Gone Girl is a liar, but she's intelligent, articulate, and fascinating. Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye is biased and self-deluded, but his voice is so distinct and his pain so palpable that we're drawn to him despite his flaws. Never make the unreliable narrator simply annoying.

Show the Impact of Their Unreliability on Others. When other characters react with confusion, concern, or contradiction, it signals to readers that something is amiss. A spouse's confused expression, a therapist's gentle probing, or a friend's worried comment all hint at the truth without stating it outright.

Decide on the Revelation Strategy. Will you fully expose the narrator's unreliability? Partially? Will you leave it ambiguous? This choice determines everything. A sudden, shocking revelation creates different impact than a gradual dawning of understanding. Some novels leave readers permanently uncertain—which can be either brilliant or maddening depending on execution.

Maintain Consistency in the Unreliability Itself. If your narrator is delusional, they should be consistently delusional in their specific way. If they're a liar, they should lie with purpose and method. Random, arbitrary unreliability feels like sloppy writing. Specific, patterned unreliability feels intentional and profound.

Use Other POV Characters Wisely. If you employ multiple points of view, let other narrators contradict or complicate the unreliable narrator's version without explicitly saying "they're lying." Show readers two versions of the same event and let them draw conclusions.

Practical Examples: The Same Scene from Different Narrator Types

To illustrate how each type might approach the same event, consider this scenario: A character named Marcus confronts his brother about borrowing money.

The Liar: "I asked Marcus for a loan, and he flew into a rage, screaming about how I'd never been responsible. I was humiliated. Of course, I didn't mention that I'd promised to repay his last loan years ago. I had no intention of doing so."

The Madman: "Marcus kept saying things that made no sense. He was angry, but I couldn't understand why. Was it about money? I think he mentioned money, but his voice kept fading in and out. I felt like I was drowning. Maybe I was drowning. It was hard to tell."

The Naïf: "Marcus was upset with me, but I'm not sure why. I remember I needed money for something important, though I can't quite recall what. He kept talking about promises, but I don't remember making any. Adults are so confusing sometimes."

The Picaro: "Marcus was upset because I borrowed money from him last year. Well, maybe it was three years. Anyway, I told him I'd pay it back when I struck it rich, which is definitely going to happen any day now. He didn't seem to believe me. Can you imagine?"

The Clown: "Marcus complained about money I'd borrowed. Or did he? I'm not entirely sure I have a brother named Marcus. Perhaps I invented him for this narrative. Let's move on, shall we?"

The Biased: "Marcus always was selfish with money. He claimed I'd borrowed from him before, but I'm certain I would have remembered such a thing. He's the type to make up stories to make himself look good. I don't know why he always has to be so dramatic."

The Impaired: "I remember Marcus saying something about money. I'd had a few drinks, so I might not be remembering this correctly. Did I owe him money? He seemed angry. I think I told him something, but the conversation is all fuzzy. I should probably apologize, but I'm not sure for what."

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

Don't make unreliability arbitrary. Every distortion should serve a purpose or stem from a clear source. Random contradictions feel like authorial error, not craft.

Don't make the narrator unpleasant to spend time with. Unreliable doesn't mean unlikable. Even the most deceptive narrator should have redeeming qualities.

Don't forget to hint at the truth. Readers should have the possibility of figuring things out before the big reveal, even if they don't take it.

Don't overexplain the unreliability. Sometimes ambiguity is more powerful than clarity. Not every question needs an answer.

Don't use unreliability as a shortcut. It's not an excuse for sloppy plotting or lazy characterization. The unreliability should deepen the story, not substitute for it.

When to Use an Unreliable Narrator

Unreliable narrators shine in several contexts: mystery and thriller fiction, where the reader becomes detective; psychological drama, where mental states drive plot; coming-of-age stories, where limited understanding is part of the journey; and experimental fiction, where narrative itself becomes a theme. They're particularly effective when exploring themes of trust, perception, memory, and identity.

However, not every story benefits from an unreliable narrator. If your plot relies on readers trusting the narrative to navigate the world, unreliability will confuse rather than intrigue. Use this technique purposefully, in service of your story's larger themes.

The Unreliable Narrator as Gateway to Deeper Themes

The most powerful unreliable narrators reveal something essential about the human condition. Holden Caulfield's biases expose the pain of adolescence. Amy's calculated deceptions explore the masks we wear in marriage. Jack's innocence in Room illuminates the resilience and fragility of childhood. The unreliability isn't merely a plot trick—it's the lens through which we examine what it means to see truthfully, to trust, to know ourselves.

When you employ an unreliable narrator, you're inviting readers into a profound conversation about the nature of truth itself. Used with skill and intention, this creates some of the most memorable, thought-provoking fiction in literature.

Closing Thoughts

Point of view is more than a mechanical choice—it is a door the writer opens for the reader, revealing not just what happens but how it feels, why it matters, and whose truth we can trust. Make your selection with intention, and let each viewpoint enrich the tapestry of your story.

© 2025 Lisa A. Moore. All rights reserved.